The U.S. Federal Reserve has once again hiked interest that it charges banks in the wake of continued elevated inflation — which peaked at 9.1 percent in June 2022 — in a bid to calm what has been a lingering problem for the overheating economy, which slowed down to 1.1 percent annualized growth in the first quarter.

Finally, the Fed has brought the Federal Funds Rate, now at 5 percent to 5.25 percent, above that of the consumer inflation rate, which remained at 5 percent in March with the April report due from the Bureau of Labor Statistics on May 10.

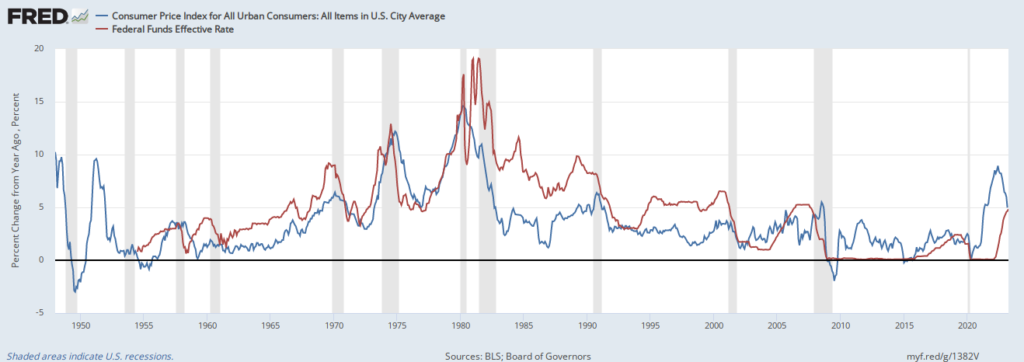

It’s about time. Usually, the central bank eventually gets its own interest rate above that of consumer inflation, but it had not started hiking interest rates until Feb. 2022, only after Russia had invaded Ukraine, further worsening the globally supply chain crisis that has been a predominant feature of the global economy since the Covid economic lockdowns and production halts. But by then inflation was already rocketing upward at 7.5 percent. In fact, by June of 2021, it was already above 5 percent, but the Fed didn’t yet move.

What was the hold up? Why didn’t the central bank begin fighting inflation in 2021 when it was perfectly clear there was inflationary pressures.

During Covid in 2020 and 2021, the Federal Reserve set interest rates to near-zero, Congress spent and borrowed more than $5 trillion and the M2 money supply increased by about $6 trillion..

Now, as a result of the tightening, the M2 money supply has actually begun to decrease from $22.05 trillion in April 2022 to its current level of $20.9 trillion, about a 5.2 percent decline. The decrease is modest in comparison to the initial expansion: it went from $15.3 trillion at the end of 2019 to the peak of $22.05 trillion, a 44 percent increase.

As for interest rates, starting from Feb. 2022 to a year later, the Fed has gone from 0.08 percent on the effective Federal Funds Rate to above 5 percent now — and they might not be through yet.

According Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, in his May 3 press conference, now the central bank is taking a wait and see approach, awaiting more data for further rate hikes: “You will notice in the statement for March we had a sentence that said the committee anticipates that some additional policy firming may be appropriate. That sentence is not in the statement anymore. We took that out. Instead we are saying that in determining the extent to which policy affirming, the Committee will take into account certain factors. So that’s a meaningful change that we we’re no longer saying that we ‘anticipate.’ And so we will be driven by incoming data meeting by meeting and we will approach that question at the June meeting.”

Additionally, Powell noted that the Board of Governors and Federal Reserve Bank presidents are anticipating a “mild recession” in the coming months: “the forecast was for a mild recession and by that I would characterize it as one in which the rise in unemployment is smaller than has been typical in modern recessions. I wouldn’t want to characterize the staff’s forecast for this meeting. But broadly similar to that.”

But, some good news is that Powell doesn’t agree per se: “that’s not my own most likely case, which is really that the economy will continue to grow at a modest rate this year.”

Which, could be why the Fed Chairman is not yet taking interest rate hikes off the table. That is, whether we’re headed into a “mild recession” or if “the economy will continue to grow at a modest rate” then inflation might not yet be in the rear view mirror yet. In April, OPEC slowed down oil production, leading prices to spike to more than $80 per barrel—which could lead to some inflation strengthening in the April report out next week. On the other hand, in May, oil prices have softened to less than $70 per barrel as demand has slowed down.

So, while there has been some hand-wringing about how “quickly” the Fed moved to raise rates, the fact is the central bank waited until inflation had already reached 7.5 percent to be begin moving interest rates, probably months too late, perhaps hoping prices would come down all by themselves as the global economy reopened. It never happened, and then Russia changed the equation when it invaded Ukraine.

To be certain, as for the pace of increase once it actually started increasing, yes, it has been one of the quicker increases of the Federal Funds Rate in recent memory in the 1990s, 2000s and 2010s, looking a bit further back in history, it looks a lot like the rate increases that combated the inflation of the 1970s and 1980s.

For example, in 1981, when the effective Federal Funds Rate rose from 14.7 percent in March 1981 to 19.1 percent in June 1981, a 4.4 percent increase.

That was dwarfed by 1980, when rose from about 9 percent in July 1980 to 19.1 percent in Jan. 1981, a 10.1 percent increase.

Or in 1979, when it rose from about 10.1 percent in April 1979 to about 17.6 percent in April 1980, a 7.5 percent increase.

Or 1973, then it rose from Sept. 1972 to Sept. 1973, from about 4.9 percent to 10.8 percent, a 5.9 percent increase.

Those were rocky times, too, but what the Fed is doing is by no means unprecedented. What was unprecedented was printing $6 trillion and simultaneously shutting the economy down and reducing production—too much money chasing too few goods.

The Fed’s rate hikes come as 10-year treasuries remain at about 3.35 percent of this writing, and 30-year mortgage interest rates are at about 6.43 percent as existing home sales remain down about 22 percent from their 2022 highs a year ago, according to the National Association of Realtors.

The news comes as the annual growth of consumer credit appears to have peaked at 8.1 percent in Oct. 2022, flattening slightly to 7.8 percent annualized by Dec. 2022 and then ticked up to 7.9 percent Jan. 2023 and now is down to 7.6 percent in Feb. 2023, which could be a sign of weakening demand. Usually, it peaks just before or at the beginning recessions, and then will slow down significantly once unemployment begins rising.

But recessions seem to be as much a matter of time and timing than anything else. At the moment the Fed seems to be disagreeing about whether we get a recession this year or next year or even further away. With that up in the air, Powell appears to be to want to keep his eye on the inflation ball that he missed in 2021. Stay tuned.