Thirty years on, questions remain as to why the UK authorities allowed the Al-Qaeda terrorist leader to run an office in the British capital for four years.

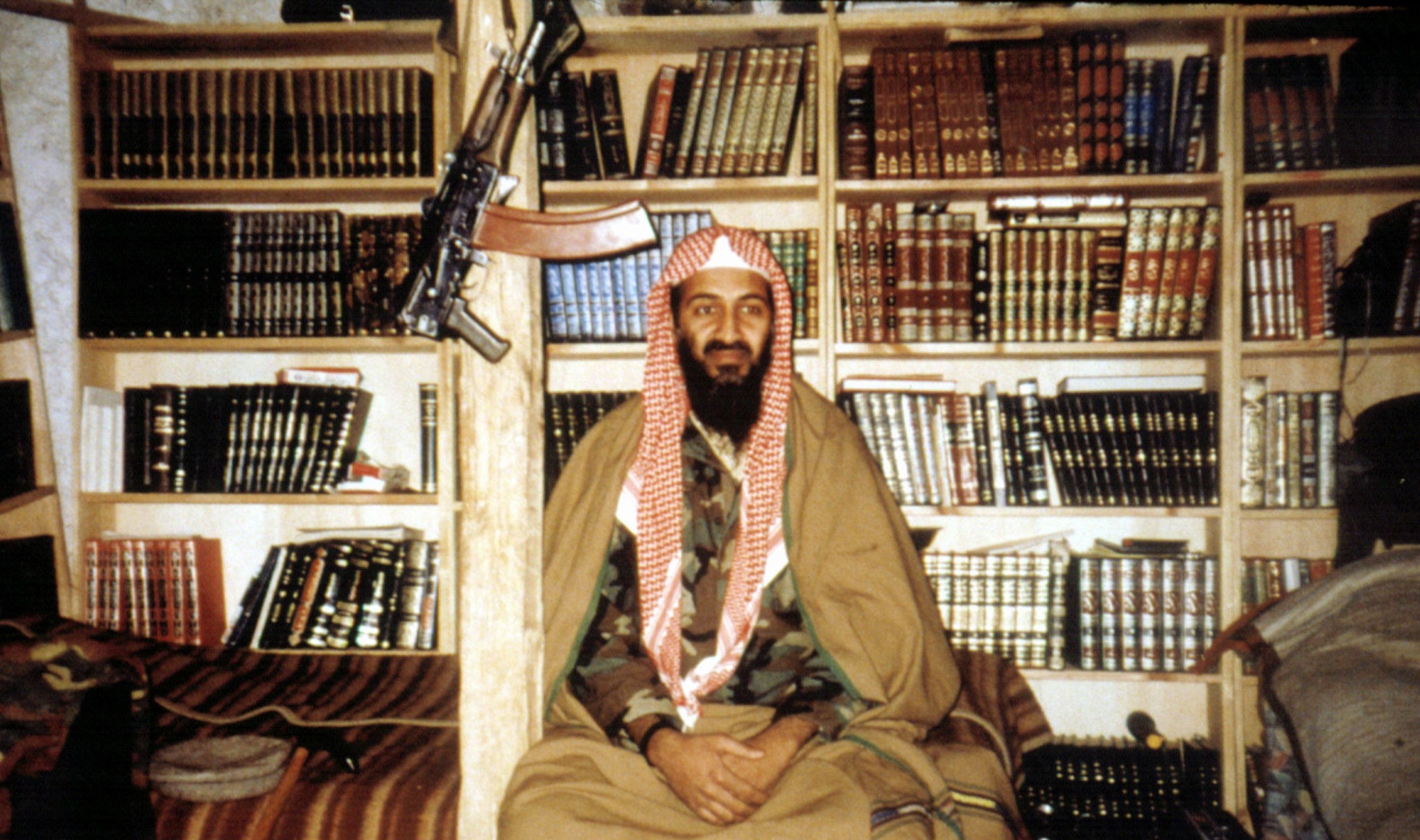

Thirty years ago this month, Al-Qaeda leader Osama Bin Laden established an office in a house in Kilburn, west London.

Seven years before 9/11, Bin Laden’s so-called Advice and Reformation Committee (ARC) was equipped with a bank of fax machines and computers which churned out dozens of pamphlets and communiqués.

The ARC lambasted the lavishness of the ruling family in Bin Laden’s native Saudi Arabia and its waywardness in promoting sharia law in the country, as well as calling for a break-up of the Saudi state.

But the purpose of the ARC went further.

US court documents noted it was “designed both to publicise Bin Laden’s statements and to provide cover for activity in support for Al Qaeda’s ‘military’ activities, including the recruitment of trainees, the disbursement of funds and the procurement of equipment and services.”

The London office also served as a communication centre for reports on military and security matters from various Al-Qaeda cells to its leadership.

A US Congressional research service report, released just after the September 11th attacks in 2001, asserted that Bin Laden even visited London in 1994 and stayed for a few months in Wembley to form the ARC, although this was never proven.

Whatever the truth of that claim, Bin Laden’s telephone billing records from 1996–8 show that nearly a fifth of his calls, 238 out of 1,100 – the largest single number – were made to London, showing the importance of this base.

It was the ARC that arranged a meeting between Bin Laden and a number of CNN journalists in March 1997.

Embassy bombings

The ARC’s staff included two members of the terrorist organisation Egyptian Islamic Jihad (EIJ) whose leader was Ayman al-Zawahiri, Bin Laden’s right-hand man.

One of the two EIJ figures was Adel Abdel Bary who, before arriving in Britain, was alleged by the US authorities to have managed Al-Qaeda training camps and guest houses. He was, however, granted asylum in the UK in 1993.

After working for Bin Laden in London, Abdel Bary was in 1998 arrested in Britain for his involvement in Al-Qaeda’s bombings of the US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in August 1998. The simultaneous blasts killed over 200 people.

He was eventually extradited to the US and jailed for 25 years.

Also arrested for his role in the bombings was the second EIJ figure in Bin Laden’s London office. This was Ibrahim Eidarous, who is alleged to have organised the EIJ’s cell in Azerbaijan in 1995 before coming to London in 1997. While in Britain, he was also granted political asylum.

On the day of the East Africa bombings, both men disseminated the claims of responsibility through faxes to the media.

Lawyers for the two men denied they had advance knowledge of the bombings but an MI5 officer, later giving evidence to an immigration appeal, stated that the faxes were actually sent before the bombings took place.

Source of intelligence

The head of Bin Laden’s ARC was the Saudi dissident Khaled Al-Fawwaz, who was also arrested by British police in September 1998 for his involvement in the East Africa bombings the previous month.

Until this point the British authorities had allowed Al-Fawwaz and the ARC to operate openly for four years.

The US indictment against Al-Fawwaz alleged that he provided Bin Laden with “various means of communications” including a satellite telephone to speak to Al-Qaeda cells, and that he visited Nairobi in 1993 and established a residence there for Abu Ubaidah, one of Al-Qaeda’s military commanders.

The evidence suggests that the ARC’s activities were initially tolerated by the British, who may have seen them as a useful source of intelligence.

Al-Fawwaz’s lawyers said he was in regular contact with MI5 from the time he came to Britain in 1994 until his arrest four years later. His meetings often lasted for three or more hours while his phone was probably tapped and his correspondence intercepted.

The BBC’s Frank Gardner wrote: “MI5 appeared to be hoping that Mr al-Fawwaz would provide them with an insight into Islamist extremists living in Britain. Mr al-Fawwaz was under the impression that his contacts with the Security Service would keep him out of trouble.”

Yet Al-Fawwaz was eventually extradited from the UK to the US in 2012 and convicted in 2015 of involvement in the embassy bombings.

Alternative leaders

What may throw further light on the British authorities’ strategy at the time is the case of another Saudi dissident in London, who was not connected to the ARC.

Saad Al-Faqih was a former professor of surgery in Saudi Arabia who had lent his medical expertise to the anti-Soviet jihad in Afghanistan in the 1980s.

He fled Saudi Arabia in 1994 and set up another opposition group to the regime, the Movement for Islamic Reform in Arabia (MIRA), in London in 1996 and was given political asylum.

Al-Faqih said he maintained “high-level contacts” with the British intelligence services and gave them advice about Saudi Arabia.

But the British secret services may have seen the ARC and other groups as providing more than just intelligence.

Asked in an interview in 2003 about living in the UK, Al-Faqih replied that the British “have discovered that betting on strategic relations with the [Saudi] regime is dangerous. It is better to have relations with the people and I assume they know how much public support we have.”

Al-Faqih also said that “the British are shrewd enough to know that the Saudi regime is doomed and they want to be in a position to deal with alternative leaders.”

It is credible that Britain may have been attempting to cultivate relations with future policy-makers in the country by tolerating these opposition groups.

While Britain has long shored up the feudal rulers of Saudi Arabia, the long-term stability of the regime has equally long been questioned. Opposition groups could act as a kind of proxy force for Whitehall in the event of upheaval in the Saudi kingdom.

Faxing Jihad

The London base allowed Bin Laden to motivate his supporters around the world. The perpetrators of the 1995 bomb attacks in Saudi Arabia, for example, had read Bin Laden’s writings after they were faxed from London.

It was also from London that various of Bin Laden’s key fatwas were sent around the world.

The ARC, for example, disseminated the English translation of Bin Laden’s August 1996 declaration of jihad against the Americans “occupying the Land of the Two Holy Places”. This called for the US to be driven from Saudi Arabia, the overthrow of the House of Saud and Islamic revolution all over the world.

Two years later, in February 1998, the ARC publicised Bin Laden’s creation of an “International Front for Jihad against the Crusaders and the Jews”, joining together a variety of terrorist groups.

However, “this caused little stir in Whitehall”, Times journalists Sean O’Neill and Daniel McGrory noted.

Interviewing Bin Laden

Also instructive is that the British and US intelligence services repeatedly turned down the chance to acquire information on Bin Laden and Al-Qaeda in the 1990s.

In early 1995, for example, the Sudanese government, then hosting Bin Laden, offered to extradite or interview him and other key operatives who had been arrested on charges of planning terrorist atrocities.

The Sudanese proffered photographs and details on various militants, including Saudis, Yemenis and Egyptians who had fought in Afghanistan against the Soviets.

“We know them in detail,” said one Sudanese source. “We know their leaders, how they implement their policies, how they plan for the future. We have tried to feed this information to American and British intelligence so they can learn how things can be tackled.”

This Sudanese offer was rejected, reportedly due to the “irrational hatred” the US felt for the Sudanese regime, as was a similar subsequent offer made specifically to MI6.

Three years later, Britain was also to ignore an arrest warrant for Bin Laden issued by Libya.

Safe in London

So safe did Bin Laden’s supporters feel in London that, in 1995, they sent overtures to the Home Office enquiring whether their leader could claim political asylum.

The then home secretary in John Major’s Conservative government, Michael Howard, later said that an investigation by his staff into Bin Laden resulted in a banning order being placed on him.

In January 1996, the Home Office sent a letter to Bin Laden stating that he be “excluded from the United Kingdom on the grounds that your presence here would not be conducive to the public good.”

Presumably, giving asylum to Bin Laden would have been a step too far in view of Whitehall’s need to placate its Saudi ally.

But the 1998 embassy bombings were not the only terrorist outrages being planned by Bin Laden, or those close to him, during the period when his London base was in operation during 1994–98.

By late 1994, the CIA was designating Bin Laden as a terrorist threat. In June 1995, an Al-Qaeda team attacked Egyptian President Mubarak’s presidential motorcade during a visit to the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa.

The following year a secret CIA analysis showed the US was aware of Bin Laden’s financing of Islamic extremists responsible for attempted bombings against 100 US servicemen in Aden in 1992. He had funneled money to Egyptian extremists to buy weapons and bankrolled terrorist training camps in northern Sudan.

After moving to Afghanistan in May 1996, Bin Laden also set up terrorist training camps there under the protection of the Taliban government.

It beggars belief that British intelligence was also not aware of Bin Laden’s activities during the period when it tolerated his London base.