In the Los Pescadores neighborhood of Maracaibo, Venezuela, tears and cheers filled the air as four young men—Mervin Yamarte, Edwuar Hernández Herrera, Andy Perozo, and Ringo Rincón—returned home after a harrowing four months in El Salvador’s notorious Center for the Confinement of Terrorism (Cecot). Their emotional reunions with family, marked by balloons in Venezuela’s national colors and the anthem “Volver a Casa” blasting through the streets, were a stark contrast to the nightmare they endured. “We lived through hell,” said 29-year-old Mervin Yamarte, wiping away tears as he hugged his six-year-old daughter.

These men were among 252 Venezuelans deported from the United States to Cecot, a maximum-security prison, under a controversial policy by U.S. President Donald Trump. Since returning to the White House in January 2025, Trump has intensified deportations, invoking the 1798 Alien Enemies Act to target alleged gang members. The U.S. accused these men of ties to the Venezuelan Tren de Aragua gang, citing their tattoos as evidence. However, all four denied any gang involvement, claiming they were arrested in Texas for immigration violations after being misidentified due to their tattoos.

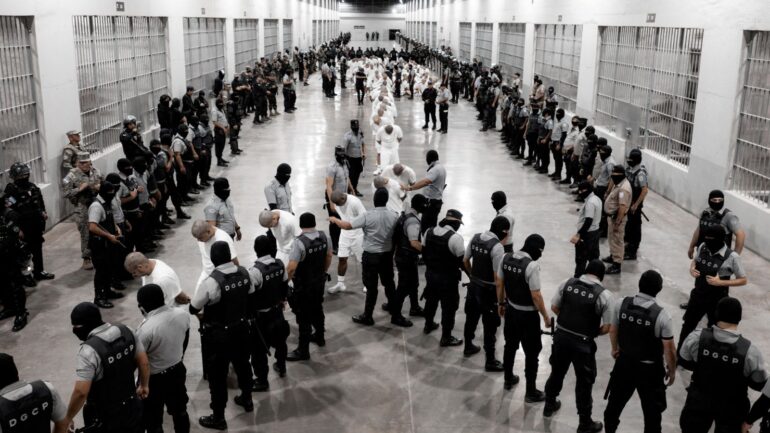

A Brutal Experience in Cecot

The men described horrific conditions inside Cecot, which opened in 2023 and has faced heavy criticism from human rights groups for overcrowding and inhumane treatment. Mervin Yamarte recounted being forced to eat “like animals” with their hands while sitting on the floor, enduring frequent beatings, and receiving no hygiene supplies. Andy Perozo, 30, said he was struck by a rubber bullet near his left eye, and that guards only provided decent food and clothing before Red Cross visits to create a false impression of humane conditions. Edwuar Hernández Herrera, 23, described sleeping on metal beds and being shot at with rubber bullets, while Ringo Rincón, 39, alleged the abuse began the moment they arrived, with beatings that left them bleeding.

Carlos Uzcátegui, another returnee from Lobatera, Venezuela, shared similar stories. After a grueling journey through the Darien Gap and working in Mexico City, he was detained in Texas while seeking asylum. Deported to Cecot, he endured beatings that left bruises on his stomach. “Every day, I woke up looking at the bars, wishing I wasn’t there,” he said, embracing his wife and stepdaughter after a 30-hour bus ride home.

A Prisoner Swap and Political Tensions

The Venezuelans were freed on July 18, 2025, as part of a prisoner exchange involving the U.S., Venezuela, and El Salvador. In return, Venezuela released 10 U.S. citizens and residents accused of plotting to destabilize the government. Venezuela’s Attorney-General Tarek William Saab denounced “systemic torture” at Cecot, including allegations of sexual abuse and rotten food, and announced an investigation into El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele and other officials. Bukele, who has denied such claims, responded on X, suggesting Venezuela’s outrage was politically motivated, as they lost leverage by releasing U.S. prisoners.

Venezuela’s government, itself under scrutiny by the International Criminal Court for alleged abuses, has aired videos of the deportees’ testimonies on state television. Meanwhile, human rights groups have documented hundreds of deaths and torture cases at Cecot, contradicting Salvadoran officials’ claims that the prison meets international standards.

A Joyous but Bittersweet Homecoming

Back in Venezuela, the returnees’ communities celebrated their release with joy and sorrow. In Los Pescadores, motorbikes roared, and families sprayed foam in celebration. Mervin’s mother decorated their home with balloons and gifts, while Edwuar’s mother, Yarelis, hung a poster reading, “Welcome home, my love!” In Lobatera, Carlos Uzcátegui’s wife, Gabriela Mora, sobbed as she clung to their fence, her living room adorned with a “Happy Father’s Day” balloon saved from June. Arturo Suárez, a reggaeton artist, told reporters in Caracas, “We met a lot of innocent people,” condemning the mistreatment they faced.

The men now face an uncertain future. Rincón plans to file a complaint through Venezuela’s Attorney-General, while Perozo, holding his children, vowed never to leave Venezuela again. For Uzcátegui, the ordeal stemmed from economic hardship that drove him to migrate. “It’s the country’s situation that forces one to make these decisions,” said Mora, reflecting on the lack of opportunities that pushed her husband to seek a better life.

A Call for Justice

The deportees’ stories highlight the human cost of aggressive immigration policies and raise questions about the use of tattoos as evidence of criminality. As Venezuela investigates alleged abuses in Cecot, and with one returnee already suing the U.S. government, the ordeal of these 252 men underscores the need for accountability and humane treatment in global migration systems. For now, the men of Los Pescadores and Lobatera are home, surrounded by loved ones, but the scars of their time in Cecot—both physical and emotional—will not fade easily.